Return

PREVIEW:

"Thousands of natural casts of dinosaur footprints occur in the roof surface of a mine in an Upper Cretaceous coal in east-central Utah. Ninety three have been removed for study. They range in length from 28 to 87.5 cm.""They often occur in trackways made by bipedal animals or are positioned around tree bases; some times the tracks are over the top of woody litter or tree roots, indicating that the animals had been walking on that material as it occurred on the swamp forest floor."

"The sediment which filled in the original footprints is usually a light-colored fluvial shale or siltstone."

"Animals living on the swamp surface made deep footprints into the peat. Before they became obliterated by the rebounding peat, a local river flooded and deposited overbank sediment into the swamp, filling the footprints and thus preserving them. Later, the peat became coal and has been removed, allowing an examination of the natural casts of these footprints and other fossils which were on the swamp surface ... Like many other Blackhawk mine roof surfaces, there are abundant fossil leaves, horizontal logs and trees in growth position which are directly associated with dinosaur footprint casts."

"The fact that certain of these track types occur in three stratigraphically different coals in the Blackhawk Formation indicates that the animals which produced them were part of the Cretaceous swamp fauna for a great length of time."

These evidences are inconsistent with:

"At the beginning of the Flood thousands of volcanoes mowed down forests all over the world. Volcanic ash fell on top of huge floating log mats. When those log mats were buried in-between the heated sedimentary layers deposited by the Flood, coal and oil were formed in a short amount of time."; as many Young Earth Creationist theorize!! Instead the evidence indicates a small minor flood situation interrupted the peat/coal formation cycle to provide these fossil footprints on top of the coal layers !!

REPRINT FROM

DINOSAUR TRACKS AND TRACES

Edited by DAVID D. GILLETTE AND MARTIN G. LOCKLEY

Cambridge University Press, 1989

DINOSAUR FOOTPRINTS FROM A COAL MINE IN EAST-CENTRAL UTAH

LEE R. PARKER AND ROBERT L. ROWLEY, JR.

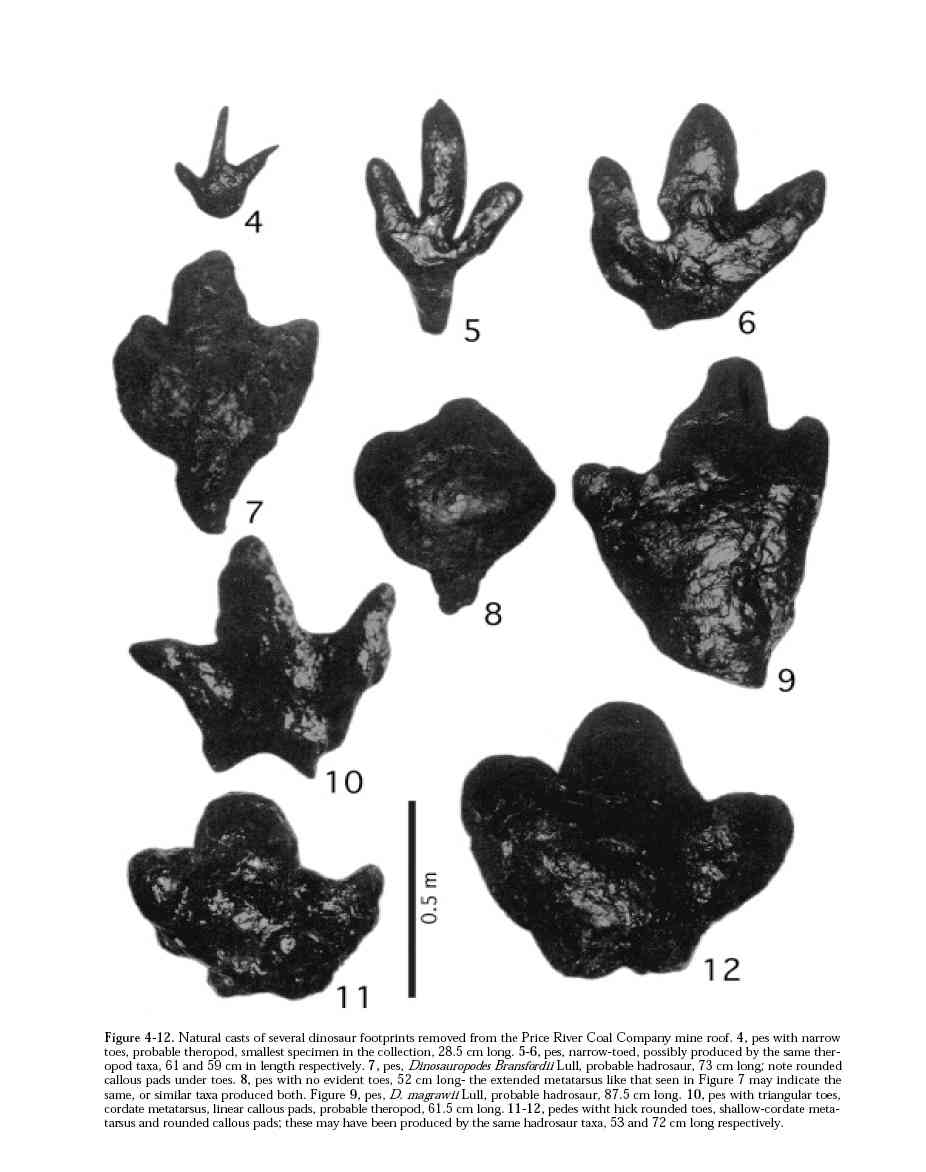

Natural casts of dinosaur footprints removed from the Price River Coal Company mine roof.

Abstract

Thousands of natural casts of dinosaur footprints occur in the roof surface of a mine in an Upper Cretaceous coal in east-central Utah. Ninety three have been removed for study. They range in length from 28 to 87.5 cm. Most are three-toed forms; only two types are four-toed. About 14 dinosaur taxa were probably responsible for producing the specimens in the collection. These tracks were made by animals which walked in the peat on the surface of a swamp; their footprints were filled by mud, silt or sand during the flooding of a local river. Most footprints are very broad with short thick toes, apparently well-adapted for walking on soft peat. Some footprint casts become loose in the mine roof and can fall, creating a hazardous condition for miners, especially in the case of tracks weighing up to 140 kg. In order to collect quality tracks, they must be chiseled from the roof rock matrix. Footprints from coal mines are well-known in central Utah and are displayed in front of the homes of miners and also in some businesses.Introduction

For twelve years one of us (Rowley) has been able to examine thousands of natural casts of dinosaur footprints as they occur in the roof surface of the Price River Coal Company mine in Spring Canyon, west of Helper, Utah. Ninety three have been removed for further study. This report briefly describes the conditions involved in the formation and collection of these dinosaur footprint casts and illustrates 14 types which have been collected.Dinosaur footprints occur in the mine roof surfaces as protrusions which hang down from the roof, sometimes as far as 30 cm. They often occur in trackways made by bipedal animals or are positioned around tree bases; some times the tracks are over the top of woody litter or tree roots, indicating that the animals had been walking on that material as it occurred on the swamp forest floor. Frequently, the roof surface is so covered with them that one track oversteps another, similar to tracks of livestock in a corral (Peterson 1924, Parker and Balsley 1989 and in prep.). Because of overstepping or incomplete depression of the foot into the peat, few tracks are of the "exhibit" quality which is desirable for removal. The sediment which filled in the original footprints is usually a light-colored fluvial shale or siltstone. The lower surfaces of most tracks are partially or completely covered with a thin layer of hard vitreous coal or a fine-grained carbonaceous siltstone, both of which have a highly polished slickenside-like surface.

The occurrence of natural casts of dinosaur foot prints from coal mines is well-known locally. It is common to see them displayed as a front yard ornament at miners' homes or as conversation pieces in reception areas of some businesses in the cities of Helper and Price. Since they can be as long as 1 m and weigh hundreds of kilograms, they are an impressive natural curiosity.

The College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum in Price has a good display of several track types. It also contains a part of the W. D. Wilson collection of many types and sizes (Lockley 1986). A collection of 30 tracks, described by Strevell (1932), is housed at the Utah State Natural History Museum, University of Utah, in Salt Lake City (Frank L. De Courten pers. comm. 1986). However, the largest collection of fossil footprint casts from coal mines of the Rocky Mountain area in terms of variety and total specimen numbers is the one illustrated in this report (made by Rowley). It numbers nearly 100 specimens, and includes 14 different footprint morphotypes. Other museums which we know to have one or several specimens include: The American Museum of Natural History, New York; California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo; The Field Institute of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois; Louisiana Polytechnic Institute, Ruston; New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Albuquerque; Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, Connecticut; The Museum of Western Colorado, Grand Junction; San Diego Museum of Natural History, San Diego, California; The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; The South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (Strevell 1932); University of New Mexico, Albuquerque (Ratkevich 1976) and Utah State University, Logan (Peterson 1924).

Geologic Setting and Paleoecology

The Castlegate D Seam which the Price River Coal Company is mining is one of several coals in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Blackhawk Formation (Doelling 1972). It was developed from a peat-forming swamp on the upper surface of the sheet-like sands of the Aberdeen Member. This member represents one of several major deltas in the formation which prograded into the Cretaceous epicontinental seaway and allowed the development of brackish and freshwater swampy environments when subaerial surfaces occurred (Balsley and Parker 1983).Animals living on the swamp surface made deep footprints into the peat. Before they became obliterated by the rebounding peat, a local river flooded and deposited overbank sediment into the swamp, filling the footprints and thus preserving them. Later, the peat became coal and has been removed, allowing an examination of the natural casts of these footprints and other fossils which were on the swamp surface (Parker and Balsley 1989 and in prep.).

Like many other Blackhawk mine roof surfaces, there are abundant fossil leaves, horizontal logs and trees in growth position which are directly associated with dinosaur footprint casts (Parker and Balsley in prep.). Recently, Rowley has collected several ferns, dicot leaves, petrified tree stumps, pelecypods and gastropods from the roof of the Price River mine, all of which made up a portion of the swamp flora and fauna at the time the footprints were made.

Removal of Tracks from the Roof Surface

As the coal is being mined it normally separates easily from the roof rock, exposing sedimentary features and fossils which might be present. Footprints can be removed where the roof rock is carbonaceous shale or siltstone; sometimes these specimens are loose and are easily pried down. The best tracks for removal are those which extend down from the roof surface at least 10 cm and have a carbonaceous layer above them. Because they are heavy and positioned slightly above head height, it is impossible for one or two persons to safely hold or catch them when they separate from the roof. Therefore, it is necessary to prepare a cushion under them and allow them to fall on it. Mine "brattice", a yellow plastic-impregnated fabric used in mines as a fire retardant and as a drape for directing ventilating air, has been effectively used for this purpose.The sedimentary matrix around the track is chiselled away with hand tools until a groove or channel is formed around it. Eventually, horizontal chiseling, up behind the track, will loosen it and allow it to drop from the roof. Specimens as large as 140 kg have been obtained in this manner without damage to the tracks. An average weight of the tracks after removal is about 45 kg. Outside the mine, extraneous coal and rock matrix can be cleaned away. Sandstone preserves footprints less frequently, but, because it makes a much harder surrounding matrix, sandstone tracks have been impossible to remove intact.

Dinosaur Tracks and Mine Safety

During the removal process it is important to consider the structural integrity of the surrounding roof to insure that large blocks of rocks do not fall. In addition, the presence of "black damp" (a deficiency of oxygen, including the build-up of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide) and methane must continually be checked, since these gases can accumulate very quickly at certain times in a working mine.

Dinosaur footprint casts which extend down from the roof several inches are a nuisance where the coal seam is thin, causing the roof to be low; mine workers continually bump their heads on them. More serious problems have existed with them since mining began in the area in the early part of the century, because they fall and kill or seriously injure mine workers. Therefore, loose footprints are bolted to the roof with a vertical drill designed to drive a 1 to 3 m long steel bolt upward into the roof rock and prevent tracks and blocks of rock from falling (Figs. 1-3). We are unaware of other lethal trace fossils, nor do we know of other circumstances where dinosaur activity has contributed to the possible death of human beings.

Morphology of the Footprints

The natural footprint casts collected from the Price River Mine seem to have been produced by several animal taxa. A few of the casts we illustrate here (Figs. 9-23) have similar morphologies, suggesting that they may have been made by the same dinosaur species, depending on age of the animal or activities at the time the footprints were made. However, it should be emphasized that all those 14 morphotypes illustrated are represented in the collection by at least four similar specimens. The only exception is the specimen shown as Figure 22, which is unique in the collection. Certain track types are represented by as many as 12 specimens including distinct left and right pes. In addition, it is clear from examinations of primary sedimentary features in the roof surface that all footprints had been pressed into peat; none were made in clastic sediment. Therefore, the morphological consistency of all specimens of each track type, each produced on the same kind of surface, suggests that the dinosaur fauna included at least 14 taxa. Most Price River specimens are three-toed; only two types are four-toed. No five-toed tracks have been observed in this mine, but they are known in other Blackhawk Formation coal mines. These tracks range in length from 28 to 87.5 cm. With a few exceptions, the foot prints, which are mostly pedes, have short toes on wide, apparently flat feet (Figs. 1, 3, 7-20, 23). This broad foot structure seems to have been adapted for walking on the soft peat of the swamp surface, similar to a snowshoe. Tracks with narrow toes occur but they are rare, both in the collection and in the actual mine roof (Figs. 2, 4-6, 21).Lull (Strevell 1932) gave Latin binomials to eight ichnospecies of the ichnogenus "Dinosauropodes" collected from a coal in the now-abandoned Standard mine (Blackhawk Formation, Castlegate A and B Coals, Doelling 1972), although Lockley and Jennings (1987) indicated that these names are not valid. Three of the species collected in the Price River mine are similar in size and shape to those in the Standard mine: D. bransfordii (Fig. 7); D. magrawii (although our specimens are not as large; Fig. 9); and D. osborni (Fig. 23). In addition, at least six species from the Price River mine have been seen in a Kenilworth mine (Blackhawk Formation, Kenilworth Coal, Parker and Balsley in prep.). These have not been described nor given Latin binomials, but include those shown here as Figures 1, 4, 7, 10, 16, and 18.

The fact that certain of these track types occur in three stratigraphically different coals in the Blackhawk Formation indicates that the animals which produced them were part of the Cretaceous swamp fauna for a great length of time. Other types, collected in only one coal bed, may be restricted in time and may prove useful as stratigraphic or paleoecologic indicators.

Diagnostic skeletal material is rarely collected in the Blackhawk Formation. What has been collected includes a carnosaur tooth (Steven F. Robison pers. comm. 1984) and the skull of Albertosaurus sp. (James H. Madsen, Jr., pers. comm. 1985; Parker and Balsley in prep.). It is thought that many of the large, flat footprint types were made by unidentified hadrosaurian species (Figs. 1, 3, 7-9, 11-20) (Strevell 1932, Parker and Balsley in prep.), certain of the narrow-toed forms were probably made by theropods like Albertosaurus (Figs. 2, 4-6, 10, 21), and a ceratopsian probably produced the four-toed specimen (Fig. 23, cf. Lockley 1986, Lockley and Jennings 1987).