from http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,808955,00.html

Palaeontologists are going to war over whether bones discovered in African desert are of an ape or a proto-human

James Meek, science correspondent

Thursday October 10, 2002

The Guardian

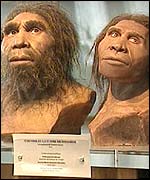

As he awoke on his last day on earth, it is unlikely Toumai thought about much more than how he would survive the following hour - let alone that, 7m years later, a bunch of ape-like creatures would be furiously discussing how much they resembled him.

Today, three months after the sensational announcement in Britain's leading scientific journal, Nature, that the oldest member of the human family had been found, the same journal publishes a sustained attack by rival scientists on the contention that Toumai's skull is, in fact, that of a hominid.

Few regions of science provoke more passion than the nature of the evolutionary journey from early ape-like mammals to homo sapiens, and other palaeontologists began grumbling about the sapience of the skull's French discoverer, Michel Brunet, as soon as his press release, with the bold claim "Toumai the Human Ancestor", hit the news media.

Today's attack on Professor Brunet and his colleagues in Nature - accompanied by a harshly worded rebuttal from Prof Brunet himself - ups the ante, putting doubts about whether the skull is hominid, ape, both or neither into the orthodox scientific arena.

Much is at stake - science, individual reputations, careers, research grants. Beneath this clash, however, lies the deeper and more disturbing question about when humans end and non-humans begin.

The skull was found in the Djurab desert of northern Chad by a team led by Prof Brunet of the University of Poitiers, who said at the time that it had been the culmination of 25 years' searching.

Prof Brunet, backed by independent scientists, claimed that the skull and jaw fragments provided enough evidence to show that we were looking into the face of the earliest hominid ever discovered.

The excitement around the discovery - it was proclaimed "a turning point", "a small nuclear bomb", and "the most important fossil discovery in living memory" - came because the skull's age put it in the middle of a 5m-year gap in our knowledge, between the accepted ancient apes and the accepted ancient hominids.

Today, another group of scientists, two based in France, two in the US, present a point-by-point demolition of Prof Brunet's case, arguing that there is no evidence to suggest Toumai was a hominid. "We believe [Toumai] was an ape," they conclude.

Prof Brunet's defenders point out that two of the authors of the critique, Brigitte Senut of France's National Museum of Natural History and Martin Pickford of the College of France, are direct rivals, having discovered their own candidate for oldest hominid in Kenya two years ago.

But another member of the anti-Brunet camp, John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin in Madison, pointed out that he had no axe to grind.

"There are social benefits that come from having the earliest hominids," he admitted. "You get your grants renewed, and the world at your door. I don't have a lot invested in it myself. My co-authors do, but I am not out digging these things up. I just read something I didn't find convincing."

Mr Hawks and his colleagues do not dispute the age of the fossil, or even its importance, but argue there is not enough evidence to put it in on the human side of the primate family tree, and much to link it with gorillas or chimpanzees.

Toumai's teeth have at least as much in common with early apes as they do with hominids, they say. Features like the large brow ridge are indeed seen in relatively recent human ancestors, but not in earlier, known hominids - meaning the brow would have to have evolved one way, then back, then evolved again to get into the human family.

Even with only part of a head to go on, critics say, the balance of evidence suggests the creature could not walk upright.

"The evidence they present is not conclusive, but there's conclusive evidence that it's not a biped, and therefore we conclude it's not a hominid," said Milford Wolpoff, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, the fourth member of the anti-Brunet group. "We think it's an ape. I suppose it could be a female gorilla. To be honest, I think it could be an ancestor of both chimps and humans before the species split, and probably this is an extinct branch."

Dr Wolpoff stressed he was not taking issue with the momentous nature of the find, only the conclusions Prof Brunet had drawn: "It's the only fossil ape we've got from between 10m years ago and today."

Prof Brunet could not be contacted for comment yesterday. In his rebuttal, he said his critics had misrepresented the dimensions of Toumai. "Wolpoff et al have described no derived ape feature of [Toumai], nor have they disproved any derived features that this species shares with later hominids."

Henry Gee, a senior editor at Nature, said that the journal had gone to enormous lengths to verify the original Brunet paper. He had visited Poitiers twice to see the skull, and the paper had been anonymously peer-reviewed by five independent scientists in the same field.

Both Prof Brunet and Dr Gee pointed out that in 1925, when Nature stunned the world with its publication of Raymond Dart's account of his discovery of a 3.3m-year-old hominid fossil in South Africa, critics said the skull was that of an ape.

Dr Gee said the critics made interesting points, but were, he felt, "barking up the wrong tree". "Whatever Toumai is, it shows a combination of features we haven't seen before in hominids or apes," he said.

Professor Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, was more cautious, pointing to growing evidence that human evolution was "bushy" rather than linear.

"It is premature to push the claims too far for any existing fossils to represent the earliest members of the human family in the present patchy state of our knowledge," he said.

Large, continuous brow ridge

· Supporters of the hominid theory say this suggests a link to more recent human ancestors. Critics point out that known early hominids, younger than Toumai, didn't have the ridge. The same is true of the creature's vertical face: could these features have evolved, de-evolved, then re-evolved?

Spine-skull intersection

· Some critics say the hole where the spine enters the skull is too far forward for Toumai to have walked upright. Supporters of the hominid theory say this cannot be known

Thickened enamel on molars

· Critics say this feature means Toumai was as likely to have been an ape ancestor - or an evolutionary dead end - as a hominid ancestor

Canine teeth

· Critics say the ratio of the distance between Toumai's canine teeth and from the canines to the back of the mouth are as chimp-like as they are hominid-like, and prove nothing