Return

Young earth theories have NO satisfactory explanation for the extensive Smoky Hill Chalk formations layered with bentonite from intermittent ash deposits blown in from active volcanic centers many hundreds of miles away !

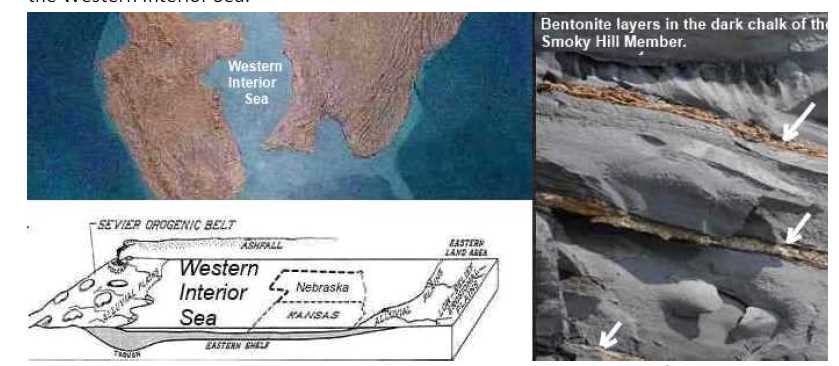

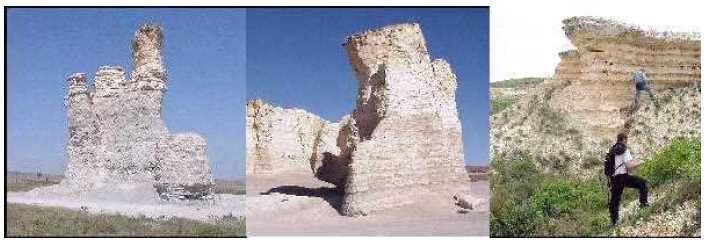

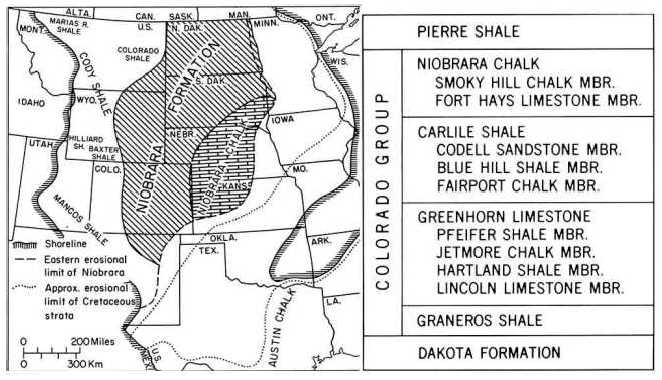

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock, a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite. Calcite is an ionic salt called calcium carbonate or CaCO3. It forms under reasonably deep marine conditions from the gradual accumulation of minute calcite shells (coccoliths) shed from micro-organisms called coccolithophores. ... Chalk has greater resistance to weathering and slumping than the clays with which it is usually associated, thus forming tall steep cliffs where chalk ridges meet the sea. ... Most cliffs of chalk have very few obvious bedding planes unlike most thick sequences of limestone such as the Carboniferous Limestone or the Jurassic oolitic limestones. This presumably indicates very stable conditions over tens of millions of years. (Wikipedia-chalk) However, the about 600 feet thick formation of the Smoky Hill Chalk member in southeastern Nebraska and northwest Kansas has more than a hundred thin layers of bentonite clay, most of which are rusty red in color, that are the result of the fall of ash from repeated eruptions of volcanoes to the west of Kansas in what is now Nevada and Utah. These ash deposits can be traced for miles across the chalk beds and have been used as marker units in describing the stratigraphy of the formation. The Smoky Hill Chalk was deposited near the center of the Western Interior Sea.

Several species of vertebrate and invertebrate marine life that lived and/or became extinct at certain times during the deposition of the chalk are useful in determining the age and biostratigraphy of widely separated exposures (See Stewart, 1990). With time the Western Interior Sea began to close, becoming shallower and narrower as the Rocky Mountains were pushed up from the west, uplifting the sea bottom as they rose. Eventually, the center of North America rose above sea level and the sediments (limestones, sandstones, shales and chalk) deposited on the basement rocks of the area then began to erode away." ( from Oceans of Kansas Paleontology.htm)

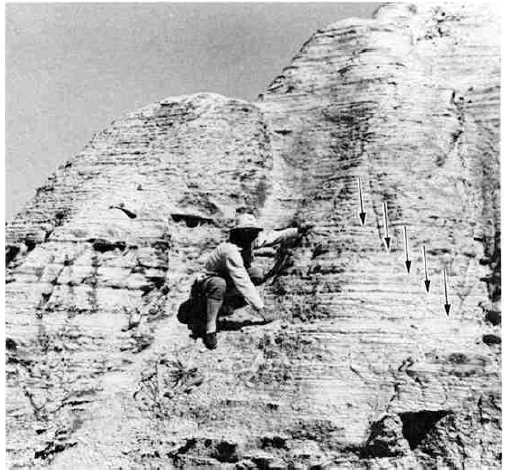

Below is an older photo showing a group of 5 bentonite seams (5 arrows). The Smoky Hill Chalk is downwind of a long chain of what were active volcanic centers that ends in Wyoming at Yellowstone.

The Pierre Shale which overlays the Niobrara Formation and the Smoky Hill Chalk also contains numerous layers of bentonite. Older photo below shows a man standing on the top layer of the Niobrara Formation with bentonite layers as light bands, but not easily seen in the poor quality photo.

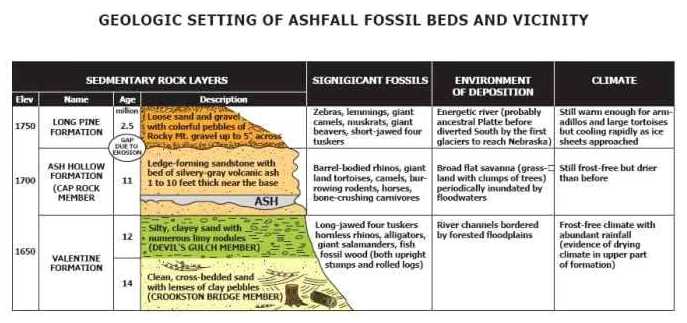

Further examples of this type of ashfall and the destruction it can cause is seen at Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park with it's unique collection of skeletons in an ash bed of 1 to 10 feet. Digging down from the top the scientists always found rhinoceroses first, then, at deeper levels, smaller hoofed animals such as horses and camels, and finally, birds and turtles. The latter were always at the very bottom of the ash bed, in a layer containing numerous footprints of rhinos and other hoofed animals. It seemed evident that the small creatures died first, then the middle-sized ones, and finally, the rhinos. The animals definitely did not die all at once; they were not (with the possible exception of the birds and turtles) buried alive. The larger animals clearly died more slowly, over a period of a few days to a few weeks. Proof that they were not instantaneously killed and buried can be seen on many skeletons, especially those of horses and camels, which often show bite marks attributed to large scavengers that must have had access to the carcasses before they were completely buried. Every fossil mammal so far discovered at the site has abnormal patches of highly porous superficial bone on various parts of its skeleton, especially on the lower jaw and the shafts of the major limb bones and ribs. Veterinarians have reported very similar growths on animals that have died of lung failure. Inhalation of large amounts of volcanic ash almost certainly caused the deaths of the Ashfall victims." ( from museum.unl.edu /ashfall )

Chemical analysis revealed that the volcanic ash has the same components as an extinct volcanic caldera in southern Idaho that geologists call the Bruneau-Jarbidge Eruptive Center 600 miles to the west and just north of the south west border between Idaho and Nevada.

Note: When Mt St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, a relative small eruption, a pocket of ash 5 to 13 cm reached the Idaho border, about 250 miles away and with smaller traces reaching Yellowstone.

The Ashfall bed is on top of a sedmentary rock layer called the Valentine Formation and below the Long Pine Formation each containing many large mammal fossils. The Smoky Hill Chalk has also been the source of thousands of fossil specimens, giant clams, rudists, crinoids, squid, ammonites, numerous sharks and bony fish, turtles, plesiosaurs, mosasaurs , pteranodons and even several species of marine (toothed) birds. ( from oceansofkansas.com)

After the interior sea was gone and Nebraska became dry the mammoth became abundant. Three species of mammoth are known from the state: the woolly mammmoth (Mammuthus primigenius), the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), and the Imperial mammoth (Mammuthus imperator). These large elephants are found in sediments near major rivers, among them the Missouri, Platte, and Niobrara. Also Nebraska was at the southern edge of the large glaciers that covered northern North America. Vast prairies dotted with lakes developed near the ice sheets, providing an ideal grassy habitat for these large grazing creatures, as well as for bison, beavers, prairie dogs, and condors. Mammoth fossils have been found in all 93 of Nebraska's counties, and it is estimated that the remains of ten mammoths lie buried in an average square mile of Nebraska landscape and it has been designated as the state fossil. The most famous discovery in the state was a 15 ton, 14 foot high specimen of the Imperial mammoth found in Lincoln County in 1922.

Bottom line: Young earth theorists such as Andrew Snelling in his article "Can Flood Geology Explain Thick Chalk Layers?" have wrestled with the problem of how hundreds of feet of chalk can form in only the time frame of the Flood of Noah (371 days) and have not really come up with a reasonable proposal ! And of course they do not consider the periodic layering of chalk formations with bentonite clay layers formed from intermittent ash deposits blown in from active volcanic centers many hundreds of miles away ! Only old earth theories allow for a satisfactory explanation for these extensive layered chalk formations !!

And Gen 2:1 " Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them." says it is all pre-Flood !!

University of Nebraska State Museum

Museum Notes Number 81.

February 1992

Ashfall: Life and Death at a Nebraska Waterhole Ten Million Years Ago

By Mike Voorhies, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology

Hundreds of skeletons of prehistoric animals have been found in a volcanic ash bed buried beneath the rolling farmlands of northeastern Nebraska. Some of the best-preserved fossil rhinos, horses, camels, and birds known anywhere have been, and are being, excavated by museum crews working in the Ashfall Fossil Beds in northern Antelope County. Unlike most fossil deposits, which consist of scattered bones accumulated over extended periods of time, the ash bed contains mostly articulated remains with bones still joined together in the proper order.Quick burial in volcanic ash accounts for the three-dimensional preservation of the skeletons of species that became extinct millions of years before they could have been seen by humans. These remarkably lifelike skeletons, some of which contain unborn young and stomach contents, give paleontologists an opportunity to reconstruct the life appearance and habits of these ancient species with an accuracy never before attainable.

The ash bed also contains abundant additional clues to the vegetation and climate of the landscape in which the rhinos and other animals lived and died. It is truly a 'time capsule' presenting us with a picture of a vanished world unrivaled in detail and clarity. This pamphlet describes some of the highlights of the first two decades of exploration of the site. It also invites you, the reader, to experience a sense of discovery of Nebraska's deep past by visiting the locality, which is now open to the public five months each year.

A New Park

Nebraska's newest state park, Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park, opened its gates on June 1, 1991. Located 6 miles north of U.S. Highway 20 between Royal and Orchard, the park is a joint project of the University of Nebraska State Museum and the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Two buildings have been constructed at the site: a Visitor Center featuring interpretive displays and a working fossil preparation laboratory and a Rhino Barn covering a portion of the fossil-bearing ash bed. Each summer paleontologists working in the Rhino Barn will continue to expose skeletons buried in the ash. The newly uncovered fossils are being left exactly as they are found. Specially constructed walkways afford visitors an unobstructed, close-up view of the paleontologists at work. When the entire 2000-square-foot area within the Rhino Barn has been excavated, plans call for extending the building to cover more of the fossil bed, only a small fraction of which is currently protected by a roof.

Discovery

The first indication that a fossil bed of major significance might lie buried on Melvin Colson's farm came to light during the summer of 1971 when I noticed the skull of a baby rhinoceros eroding from the wall of a ravine at the edge of a cornfield on Mr. Colson's property.

What made the find so unusual was that the skull and lower jaws were in perfect articulation and that the fossil was completely embedded in soft, distinctly layered volcanic ash.

I had originally visited the Colson farm in 1969 as part of a long term study of the geology and paleontology of the Verdigre valley. Verdigre Creek and its many tributaries have carved nearly 500 square miles of Knox, Antelope, and Holt counties into a network of rugged hills and ravines. My wife, Jane, and I located and mapped more than 200 fossil-producing sites in this area between 1968 and 1975. What drew us to the Colson farm was a cliff nearly 100 feet high with a layer of very hard sandstone at the top. Like previous generations of fossil hunters we had learned to expect bones in this particular sandstone, known to geologists as the Cap Rock.

Jane and I found a few fragmentary fossils on our first visit--nothing exciting but enough to prompt return trips in succeeding years. Our attention eventually shifted away from the high cliff to a series of less spectacular outcrops that trickled through Mr. Colson's pasture. It was here, on a deeply gullied hillside recently swept free of soil and debris by torrential rains, that a routine afternoon of prospecting turned into a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

Excitedly, I brushed the ash away from the little skull, first from the oversized teeth, then farther back, looking for evidence that the rest of the skeleton might be there. It was. Just as the old song has it:

"The head bone connected to the neck bone,

the neck bone connected to the back bone,

the back bone connected to the hip bone..."

Not only did this first rhino turn out to be intact but other equally good skeletons seemed to be extending back into the hill, covered by ten to twenty feet of ash and sandstone. Although it was difficult to resist the impulse to dig straight back into the ash bed and see what else was there, past experience had taught me that this would not only have endangered the fossils (and maybe the digger!) but also would have destroyed important evidence about the origin of the deposit.

Initial Excavations 1977-1979

Because of the unusual nature of the site, special care had to be taken in exploring it. Before any extensive digging could be done, it was necessary to learn as much as possible about the geologic relationships of the fossil-bearing bed.

A series of shallow pits excavated with a trowel revealed far too large an area to be worked by one person. In order to obtain funding for a large-scale excavation I needed to document the extent and significance of the deposit so in June 1977 a small crew from the Museum helped me shovel off the overburden from 20 square meters of the fossil bed and collect several skeletons.

The National Geographic Society agreed to support a larger-scale excavation of the site when I sent them photographs and descriptions of the 1977 test excavation which showed that skeletons of horses as well as rhinos (one containing a fetus) were present in the deposit. With funding from the Society I was able to hire a crew of eight students and spend the summers of 1978 and 1979 excavation the ash bed. With Mr. Colson's permission we had a bulldozer gradually remove the sandstone and upper part of the ash bed over an area of about 600 square meters adjacent to our 1977 test excavation. (First, of course, we probed these upper beds to make sure they contained no fossils!)

After gridding the bulldozed area into a series of 3 by 3 meter squares we began to carefully remove the remaining (lower) portion of the ash bed where the skeletons, we believed, should lie. The results exceeded even our most optimistic expectations. Not only did we find dozens of additional rhinoceros and horse skeletons but also remains of camels, birds, turtles, and small saber-toothed deer. It became clear that a major disaster, claiming hundreds of victims, had occurred at the site.

What Happened?

As excavation proceeded through the summer months of 1978 and again in 1979 the museum team collected any and all kinds of information that might help us understand the origin of this deposit, apparently the only one of its kind in the world. Like detectives at the scene of a crime we paid special attention to the position of the bodies--photographing and sketching each one before encasing it in a plaster cast and removing it to the laboratory for further analysis.

It became clear early on that there was a definite pattern to the arrangement of the skeletons in the ash bed. Digging down from the top we always found rhinoceroses first, then, at deeper levels, smaller hoofed animals such as horses and camels, and finally, birds and turtles.

The latter were always at the very bottom of the ash bed, in a layer containing numerous footprints of rhinos and other hoofed animals. It seemed evident that the small creatures died first, then the middle-sized ones, and finally, the rhinos. The animals definitely did not die all at once; they were not (with the possible exception of the birds and turtles) buried alive.

The larger animals clearly died more slowly, over a period of a few days to a few weeks. Proof that they were not instantaneously killed and buried can be seen on many skeletons, especially those of horses and camels, which often show bite marks attributed to large scavengers that must have had access to the carcasses before they were completely buried. Every fossil mammal so far discovered at the site has abnormal patches of highly porous superficial bone on various parts of its skeleton, especially on the lower jaw and the shafts of the major limb bones and ribs. Veterinarians have reported very similar growths on animals that have died of lung failure. Inhalation of large amounts of volcanic ash almost certainly caused the deaths of the Ashfall victims.

Further Reading

Articles on the Ashfall site can be found in National Geographic (January, 1981) and Nebraskaland (June, 1990) magazines. More technical data are presented in Science (vol. 206, pp. 331-333) and National Geographic Research Reports (vol. 19, pp. 671-688). General information on ancient mammals is available in Mammal Evolution an Illustrated Guide by R.J.G. Savage and M.R. Long (Crown Publications, 1986).